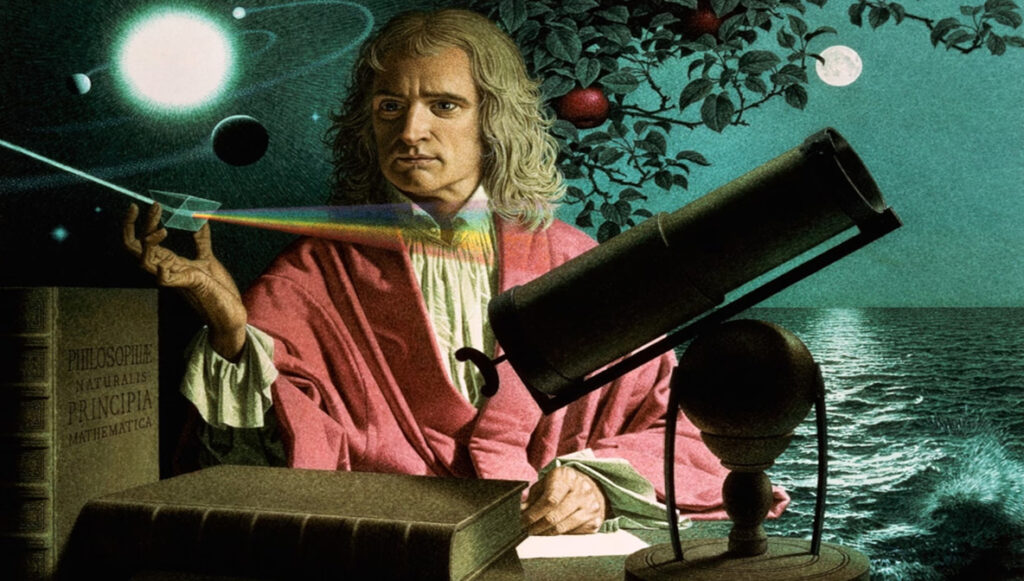

Newton’s influence on the scientific revolution and the future of science cannot be overstated. His work in physics laid the foundation for the Age of Enlightenment and set the stage for the Industrial Revolution. His laws of motion and universal gravitation remained the standard for classical mechanics until the development of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity in the 20th century.

Isaac Newton’s genius was not just in his discoveries, but in the way he unified different strands of knowledge into a cohesive framework. He built a system of understanding that transcended his own time and continues to be the bedrock of modern science. His ability to synthesize knowledge across various fields, from physics to mathematics to theology, set him apart as a towering figure in the intellectual history of humanity.

Full Biography of Sir Isaac Newton

Name: Sir Isaac Newton

Born: January 4, 1643 (Julian calendar) / January 14, 1643 (Gregorian calendar)

Died: March 31, 1727 (April 20, 1727 in Gregorian calendar)

Place of Birth: Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England

Occupation: Mathematician, Physicist, Astronomer, Philosopher, Alchemist

Nationality: English

Famous For: Laws of Motion, Law of Universal Gravitation, Calculus, Optics

Early Life and Family

Isaac Newton was born on January 4, 1643, in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England, to Hannah Ayscough Newton and Isaac Newton Sr. His father, Isaac Sr., was a prosperous farmer who died three months before his son’s birth. Isaac Newton Sr.’s death left Newton’s mother, Hannah, to raise him alone.

At the age of three, Isaac was left in the care of his maternal grandmother while his mother remarried, and her second marriage led to a strained relationship with her son. His childhood was marked by an interest in mechanical devices and building, showing early signs of his inventive genius.

Newton attended The King’s School in Grantham from age 12 to 17. Afterward, he enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1661. His time at Cambridge was crucial in his intellectual development. Initially, he focused on classical studies but later turned to mathematics, physics, and astronomy, studying the works of great scientists like Galileo, Descartes, and Kepler.

Isaac Newton’s academic path was defined by a strong curiosity about the natural world and a passion for understanding the underlying principles of the universe. At Trinity College, Cambridge, Newton studied the works of the classical scholars, such as Aristotle and Ptolemy, but he quickly became frustrated with their reliance on outdated theories. Instead, he turned to the more recent work of Galileo Galilei, Johannes Kepler, and René Descartes, whose ideas about motion, the structure of the universe, and mathematics fascinated him.

While at Cambridge, Newton’s scientific genius was recognized by the famous mathematician John Collins and philosopher Henry More. Newton’s intellectual journey at this stage took him through a number of key developments, including the early formation of ideas that would later become his most famous theories.

Academic Career and Contributions

Trinity College and Early Research (1665-1667)

Newton’s time at Cambridge was disrupted by the outbreak of the Great Plague in 1665. During the two years he spent at home in Woolsthorpe, he conducted some of his most famous experiments, which led to his groundbreaking work in mathematics and physics. This period is often referred to as his “Annus Mirabilis” or “Year of Wonders.”

- Optics: Newton began studying the nature of light and color. He discovered that white light is made up of a spectrum of colors, which he demonstrated using a prism to split light. He also formulated the theory that light is made of particles (corpuscular theory of light), challenging the prevailing wave theory.

- Calculus: In 1666, Newton developed the early concepts of what would later be called calculus. Although he did not publish his findings until later, the methods of differentiation and integration that he devised were revolutionary in mathematics. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a German mathematician, independently developed calculus around the same time, leading to a bitter dispute over priority.

- Gravitation: Newton also began to formulate his ideas on gravity during this period. The legendary story of Newton’s discovery of the law of gravity, in which he saw an apple fall from a tree and wondered why it fell straight down, is often recounted (though its veracity is debated). His insight into gravity led him to propose the universal law of gravitation, suggesting that every particle of matter in the universe attracts every other particle with a force that is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

Career at Cambridge (1667–1700)

Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667 and was elected as a fellow of Trinity College. His research on optics continued, and he published his first significant work, Opticks, in 1704.

In 1672, Newton was elected a member of the Royal Society after he submitted a paper on optics that received widespread praise. In the same year, he became a professor of mathematics at Cambridge. His work on gravitation culminated in the formulation of his laws of motion and universal gravitation, which he published in his landmark book, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), in 1687. This work laid the foundation for classical mechanics and revolutionized the study of physics.

Major Achievements

- Laws of Motion: Newton’s Three Laws of Motion are central to classical mechanics:

- An object at rest will remain at rest, and an object in motion will remain in motion at constant velocity unless acted upon by a net external force.

- The force acting on an object is equal to the mass of the object multiplied by its acceleration (F = ma).

- For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

- Law of Universal Gravitation: Newton’s law of gravitation stated that every object in the universe attracts every other object with a force that is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

- Calculus: As mentioned, Newton developed calculus as a mathematical tool to describe motion and change. He applied it to describe the orbits of planets, the behavior of fluids, and even the laws of motion.

- Optics: Newton made significant contributions to optics, explaining the behavior of light and the colors of the rainbow. His work on the nature of light laid the groundwork for modern optics.

Key Publications

- Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (Principia) (1687)

This is considered one of the most important works in the history of science. In this work, Newton formulated his laws of motion and universal gravitation, providing a comprehensive framework for understanding the motion of celestial bodies and objects on Earth. - Opticks (1704)

This work on optics presented Newton’s findings on light and color. It was influential in the study of optics and remains important in the field even today. - A Treatise of the System of the World (1702)

This was a follow-up to his Principia and expanded his work on celestial mechanics.

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (The Principia)

Perhaps Newton’s most monumental work, the Principia (published in 1687), was the first time a comprehensive theory of the universe was presented in a unified way. In this work, Newton described the three laws of motion that explained how objects move under various forces and proposed his universal law of gravitation to explain how celestial bodies move.

Principia was more than just a scientific book; it was the culmination of over 20 years of study. The mathematical rigor in Newton’s formulation of these laws was unprecedented and would shape the study of physics for centuries. The implications were revolutionary:

- It showed that the motion of both earthly objects (such as falling apples) and celestial bodies (such as planets orbiting the Sun) could be explained by the same set of physical laws.

- It helped confirm heliocentrism (the Sun-centered solar system) and demonstrated the infinite reach of gravity, where every object in the universe exerted a gravitational pull on every other object, no matter the distance.

Opticks (1704)

Newton’s contribution to optics was transformative. In his work Opticks, he described experiments with light, refraction, and the nature of color. He performed an experiment where he passed a beam of white light through a prism, showing that it split into the colors of the rainbow. This demonstrated that white light is a mixture of different colors and fundamentally challenged the prevailing theory that white light was a pure form of light.

Newton also introduced the concept of corpuscular theory, which posited that light was composed of particles (or “corpuscles”), rather than waves, as had been suggested by Christiaan Huygens. This idea would be at the heart of the ongoing debate in optics and wave-particle theory until the 20th century.

Alchemy and Theological Interests

Beyond physics and mathematics, Newton had a deep interest in alchemy and theology, subjects that were often intertwined for him. He believed that understanding the natural world was essential to understanding God’s design for the universe. His religious views were complex:

- He was a devout Christian, though not in a traditional sense. Newton denied the doctrine of the Trinity, which led him to be branded as a heretic by many in the Anglican Church.

- His study of alchemy was extensive, and he spent years trying to uncover the secrets of the philosopher’s stone and transmutation. However, much of his alchemical work was not made public, and it was only in the 20th century that historians fully appreciated the extent of his engagement with mystical thought.

His theological writings were less known during his lifetime, and many were not published until after his death. His belief in a divine presence and an ordered, rational universe led him to conclude that the laws of nature were not merely mechanical but deeply connected to a divine order.

The Newton-Leibniz Calculus Controversy

One of the most significant controversies in Newton’s life was his dispute with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz over the invention of calculus. In the late 17th century, both men developed calculus independently, though Leibniz published his work earlier than Newton.

In the 1690s, a heated debate erupted between their followers, with accusations of plagiarism flying. The Royal Society, which Newton presided over, eventually sided with him, declaring that he had invented calculus first. However, historians now believe that both men arrived at similar ideas independently. While Newton developed his ideas around 1666, he did not publish them until later, while Leibniz’s first papers appeared in the 1680s. Despite the dispute, both men’s contributions are considered foundational to modern calculus.

Newton’s Political and Administrative Career

In the later stages of his life, Newton transitioned from theoretical science into public service, particularly through his role at the Royal Mint.

Warden of the Royal Mint (1696-1699)

Newton was appointed to the position of Warden of the Royal Mint in 1696, and he quickly moved to root out counterfeiters, who had been undermining the currency in England. He implemented strict measures, even going so far as to interrogate and imprison suspected counterfeiters. His efforts helped restore confidence in the English currency and were a significant part of his legacy as an administrator.

Master of the Mint (1699-1727)

In 1699, Newton was promoted to Master of the Royal Mint, a prestigious and powerful position that he held until his death. He oversaw the production of coins and worked to modernize the English currency. Under his leadership, the Mint adopted new security features on coins, which helped in curbing the problem of counterfeiting.

Political Life

Newton also had a brief political career, serving as a Member of Parliament for the University of Cambridge from 1689 to 1690 and again in 1701. However, his involvement in parliamentary affairs was largely ceremonial, and he was known to speak very little during sessions.

Later Life and Career

- Warden of the Royal Mint (1696-1699): In 1696, Newton took on the role of Warden of the Royal Mint, where he was responsible for overseeing the coinage of England. He was later appointed Master of the Mint in 1699, a position he held until his death. Newton was instrumental in reforming the English coinage, fighting against counterfeiters, and implementing policies that helped stabilize the British economy.

- Member of Parliament: Newton briefly served as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons. He represented the University of Cambridge in 1689 and 1701, although his contributions to parliamentary debates were minimal.

- Religious Views: Newton held unorthodox religious views and spent a great deal of time studying biblical prophecy and alchemy, although these works were not as widely published. He rejected the doctrine of the Trinity and was deeply interested in esoteric subjects.

Awards and Honors

- Knighted by Queen Anne (1705): Newton was knighted by Queen Anne for his contributions to science, making him Sir Isaac Newton.

- President of the Royal Society (1703-1727): Newton served as President of the Royal Society, an influential institution in the scientific community.

- Copley Medal: He was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society in 1705 for his outstanding contributions to science.

- Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences: He was also elected as a foreign member of this prestigious academy in 1712.

Personal Life

Newton never married and had no known children. His personal life was characterized by intense focus on his work and a certain degree of solitude. He was often described as having an irritable and temperamental personality.

Though largely introverted, Newton had some personal relationships, notably with fellow scientists and intellectuals such as Robert Hooke (with whom he had a famous dispute over optics) and Gottfried Leibniz (in their calculus priority dispute).

Later Years, Honors, and Final Days

As a renowned figure in both scientific and political spheres, Newton’s later years were marked by recognition and reverence:

- He was knighted by Queen Anne in 1705 for his groundbreaking work in science. This honor cemented his status as one of England’s most celebrated figures.

- He continued to serve as President of the Royal Society from 1703 until his death in 1727, guiding scientific discourse in England.

- Newton’s reputation grew beyond the borders of England, and by the time of his death, he had become a symbol of the intellectual Renaissance, admired across Europe.

Newton spent the last years of his life as an intellectual elder statesman, respected and revered by the scientific community. His focus remained on writing and refining his earlier work

Death and Legacy

Newton died on March 31, 1727, at the age of 84, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. His funeral was attended by many of England’s most prominent figures, including the Archbishop of Canterbury and members of the Royal Society.

Newton’s legacy is immeasurable. His laws of motion and universal gravitation formed the foundation of classical mechanics and greatly influenced later developments in physics, including Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. His work on light and optics paved the way for the field of modern physics, and his contributions to mathematics laid the groundwork for much of calculus and advanced mathematics.

Fun Fact: The Newton Apple

While the story of the apple falling from the tree has become a popular anecdote about how Newton discovered the law of gravity, it is likely a myth or simplification. However, it does illustrate Newton’s reflective nature and his ability to apply abstract thought to everyday occurrences. Newton himself mentioned the apple incident in letters but never presented it as the defining moment of his discovery.

Conclusion

Isaac Newton’s life was marked by his revolutionary discoveries and his intellectual pursuits. His work in physics, mathematics, and optics laid the foundation for much of modern science, and his insights into the natural world remain integral to our understanding of the universe. His dedication to his work, his contributions to various fields, and his legacy as one of the greatest scientific minds in history make him a towering figure in the history of human thought.